Prompt Poetry: The Art of Challenging Language Models

In an increasingly visual world, text has unexpectedly made a comeback in AI art. The skill of writing effective prompts is crucial for success or failure when generating images using AI. There are numerous theories, guides, tutorials, and self-proclaimed experts who aim to teach you how to master the algorithm and create the perfect image. However, even the creators of AI models often don’t fully understand what happens inside the black box or how an AI assembles images—it remains mostly guesswork.

There is, of course, a basic structure that allows you to create images that come close to your desired outcome. The initial words in your prompt usually receive the most focus in the resulting image. You can use various keywords to describe style, lighting, color, mood, era, and more. Additionally, AI tools have learned from existing online images, enabling them to recognize patterns. Consequently, common motifs that already have abundant examples can be recreated more effectively than rare or unusual ones. For instance, an image of a beautiful woman on the beach is more likely to turn out well than one of an elderly woman in a wheelchair on the same beach. However, by default, the people in generated images tend to appear happy and healthy, portraying a stereotypical and superficial view—akin to stock photos—because that’s what comprises a significant portion of the training data.

But for artists, it’s precisely the uncommon, the odd, and the uncharted that they want to explore. Breaking boundaries and patterns to create images that no one has seen or imagined before is the goal. To achieve this, artists must overcome two obstacles: the language barrier and the algorithms of image generators. Your prompt is interpreted by a language model, and then the text is translated into an image. In both cases, you must try to bypass the stereotypes, clichés, and patterns embedded in the models.

Interestingly, the image generator often interprets the text not exactly as you write it but rather as it believes it should be. There seems to be an autocorrect mechanism at play. For example, if you write, “a cat playing with a mouseball under a tree,” you’ll likely get an image of a cat playing with a mouse and a ball, not a ball shaped like a mouse. The latter is less common and therefore has lower likelihood in the model. As an artist, you’d naturally want to see the mouseball in the image.

The question is: How can we challenge language models and circumvent their built-in rules? Could poetry, with its playful use of language, metaphors, and unexpected expressions, be a way forward? Below, I’ve created images based on poetry, using DALL-E 3 as a starting point.

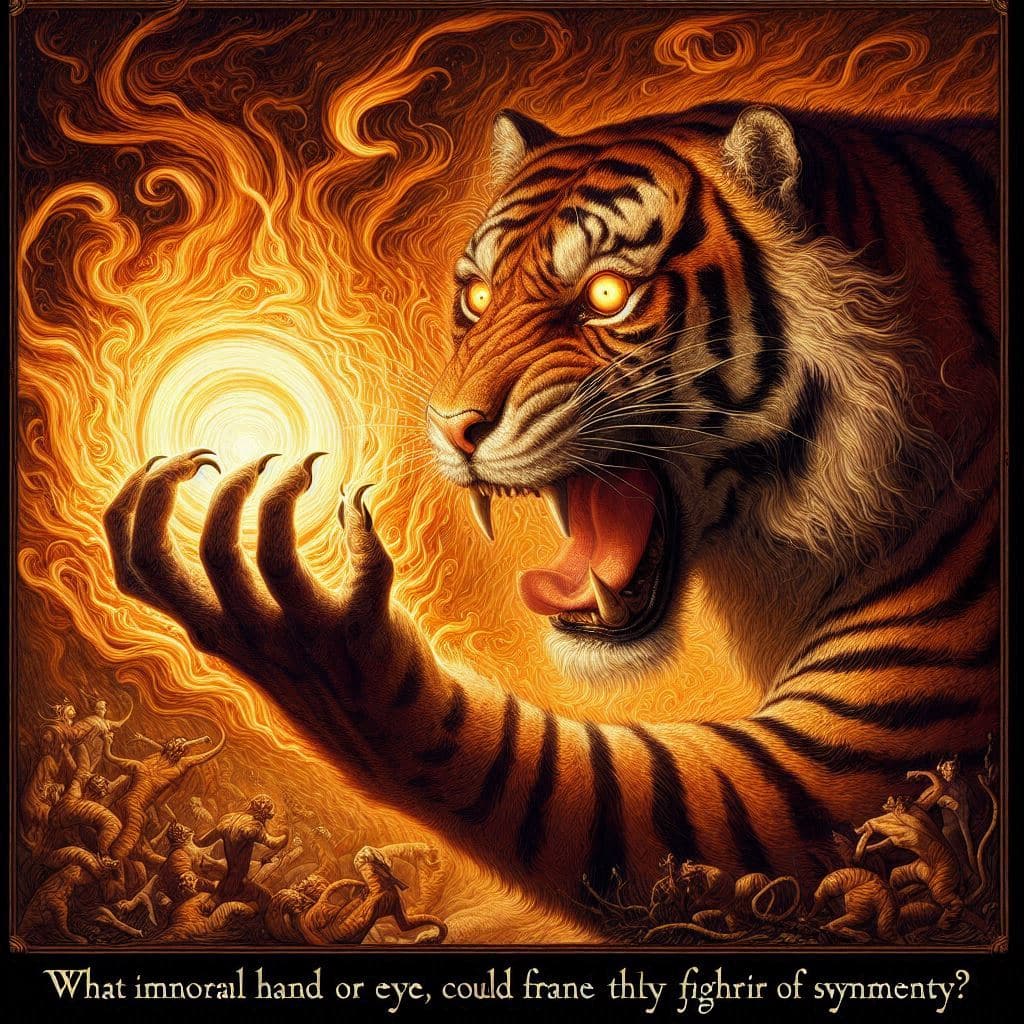

For instance, if we let AI interpret the first lines of William Blake’s famous poem “The Tyger”:

“Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry? “

The resulting image is interesting but not particularly unexpected. Perhaps the poem is too traditional? Now, let’s see what happens when we challenge the AI with more modernist poetry, such as the opening lines of Ezra Pound’s “Canto I”:

“And then went down to the ship,

Set keel to breakers, forth on the godly sea, and

We set up mast and sail on that swart ship,

Bore sheep aboard her, and our bodies also”

Contrary to expectations, the image becomes much more traditional, resembling a 19th-century maritime painting. Although it’s a bit odd to see sheep walking on water, the composition is otherwise quite stereotypical.

Finally, let’s experiment with nonsense words, which the AI model likely hasn’t encountered much. Here are the first lines from Dadaist Hugo Ball’s poem “Karawane”:

”jolifanto bambla o falli bambla

großiga m'pfa habla horem

egiga goramen

higo bloiko russula huju”

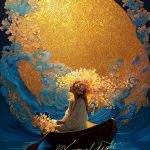

Indeed, we get an intriguing composition, but a bear playing the trumpet is something we’ve seen before. If we ask ChatGPT to translate the nonsense poem into English, we get the following translation: ‘Elephants dance around in a circle with golden caps on their heads, eating pineapple, and blowing bubbles with their trunks.’ It seems that the language model attempts to translate the words into understandable language. In some cases, it associates ‘bambla’ with ‘bear,’ and in others, ‘jolifanta’ with ‘elephant.’ Interestingly, the resulting image of the second translated prompt seems reminiscent of a children’s book.

Now, let’s combine a line from Hugo Ball’s nonsense poem ‘Karawane’ with a prompt about a beautiful woman by the sea. We might expect an unexpected outcome:

‘a higo beautiful bloiko woman russula at the huju sea’

Contrary to our expectations, we end up with an even more stereotypical image of a woman by the sea. It’s as if the language model simply discards all the nonsense words, and the strong association with a beautiful woman by the sea dominates the result.

It appears that poetry prompts don’t necessarily lead to significantly different or innovative images. Are we confined within the language model’s boundaries, with no possibility of tricking the system into creating something different?

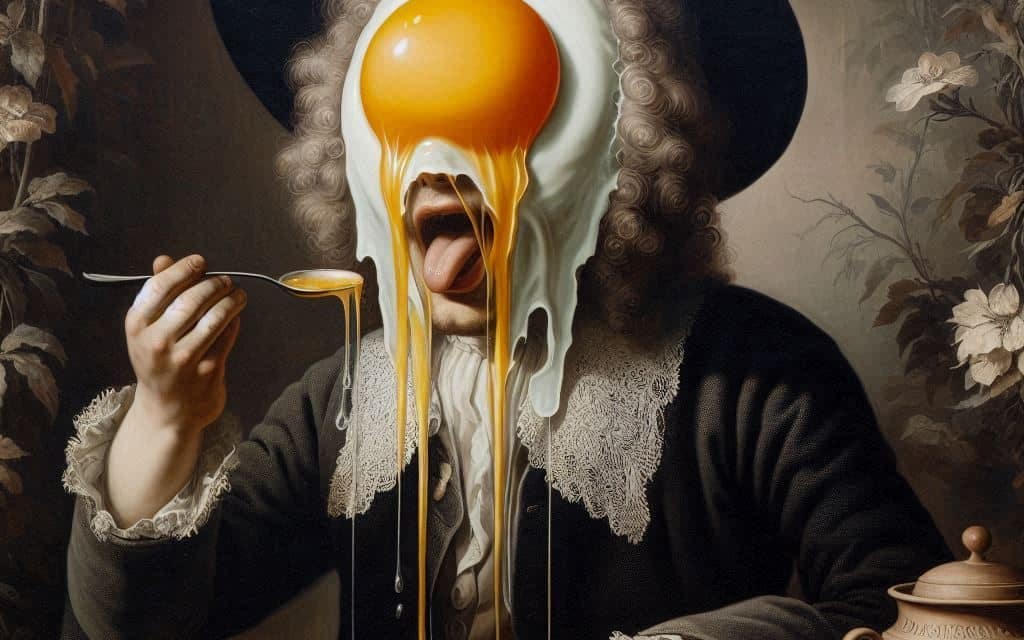

In my personal experience, I’ve often started with various historical art epochs already well-represented in the training data and then added something unexpected yet familiar—like an egg yolk or a vacuum tube—to create interesting and captivating images. Combining two concepts that are strongly ingrained in the model but don’t typically go together seems to encourage competition and fusion, resulting in novel creations. For instance, an 18th-century painting of a man with a flowing egg yolk for a head. When combining two words—one dominant in the language model and the other weaker—the result often emphasizes the stronger word, such as a beautiful woman by the sea.

To create unique images, the secret lies in creativity, experimentation, and pushing the boundaries set by the systems. Discovering the loopholes and weaknesses allows us to craft something new that nobody thought possible. And that, after all, is the exciting and adventurous part of the creative process, but it can also be frustrating.

A beautiful woman on the beach and a elderly woman in a wheelchair on the beach

William Blake’s famous poem “The Tyger”:

“Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry? “

Ezra Pound’s “Canto I”:

“And then went down to the ship,

Set keel to breakers, forth on the godly sea, and

We set up mast and sail on that swart ship,

Bore sheep aboard her, and our bodies also”

Hugo Ball’s poem “Karawane”:

”jolifanto bambla o falli bambla

großiga m'pfa habla horem

egiga goramen

higo bloiko russula huju”

ChatGPT translation of Hugo Ball's poem: ‘Elephants dance around in a circle with golden caps on their heads, eating pineapple, and blowing bubbles with their trunks.’

Comments